Lettrist International : 1945 – 1957

was founded in 1945 in Paris by the romanian Jean-Isidore Isou. It was mainly a reaction against Andre Breton’s dictatorial control of surrealism and it’s movement away from its conceptual origins in dada to mysticism.

The lettrists worked on the level of the type as the heart of an visual language, which was the base of their new culture. Isou, along with Maurice Lemaitre, worked out a notation which allowed to performe their poetry also with choral groups. Their ‘Lexique Des Lettres Nouvelles‘ was a sonic alphabet of about 130 sounds from which they composed their poetry.

A group of lettrists took an active part at the First World Congress of Liberated Artists (with the slogan ‘The International Movement for an Imagine Bauhaus’) 1956 at Alba (Italy). They published in the time from June 1954 to November 1957 29 numbers of their journal Potlatch. The last issue got the subtitle ‘Bulletin d’information de l’internationale situationiste’.

Situationist International : 1957 – 1972

On a further conference in Italy, on 27. April 1957 at Cosio d’Arroscia, where eight men and women from different european countries founded the Situationist International (SI).

Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio, Piero Simondo, Elena Verrone, Michèle Bernstein, Guy Debord, Asger Jorn, Walter Olmo

Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio, Piero Simondo, Elena Verrone, Michèle Bernstein, Guy Debord, Asger Jorn, Walter Olmo

Some of the founders came from radical art groups that had emerged around 1950 but were still almost completely unkown at that time: COBRA, called after the magazine of a northern-european (Copenhagen – Bruxelles – Amsterdam) group of experimental artists and of course members from the Lettrist International in Paris.

In its first phase the SI developed a number of ideas, which had their origins in the lettrism, like ‘urbanisme unitaire’ and ‘psychogeography’. Further SI-definitions are:

Constructed Situation: A moment of life concretely and deliberately constructed by the collective organization of a unitary ambiance and game of events.

Situationist: Having to do with the theory or practical activity of constructing situations. One who engages in the construction of situations. A member of the SI.

Situationism: A meaningless term improperly derived from the above. There is no such thing as situationism, which would mean a doctrine of interpretation of existing facts. The notion of situationism is obviously devised by anti-situationists.

Psychogeography: The study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour on individuals.

Psychogeographical: Relating to psychogeography. That which manifests the geographical environment’s direct emotional effects.

Psychogeographer: One who explores and reports on psychogeographical phenomena.

Derive: A mode of experimental behavior linked to the conditions of urban society: a technique of transient passage through various ambiances. Also used to designate a specific period of continuous deriving.

Unitary Urbanism: The theory of the combined use of arts and techniques for the integral construction of a milieu in dynamic relation with experiments in behaviour.

Detournement: Short for detournement of pre-existing aesthetic elements. The integration of present or past artistic production into a superior construction of a milieu. In this sense there can be no situationist painting or music, but only a situationist use of these means. In a more primitive sense, detournement within the old cultural spheres is a method of propaganda, a method which testifies to the wearing out and loss of importance of those spheres.

Culture: The reflection and prefiguration of the possibilities of organization of everyday life in a given historical moment; a complex of aesthetics, feelings and mores through which a collectively reacts on the life that is objectively determined by it’s economy. (We are defining this term only in the perspective of the creation of values, not in that of the teaching of them.)

Decomposition: The process in which the traditional cultural forms have destroyed themselves as a result of the emergence of superior means of dominating nature which enable and require superior cultural constructions. We can distinguish between an active phase of the decomposition and effective demolition of the old superstructure – which came to an end around 1930 – and a phase of repetition which has prevailed since then. The delay in the transition from decomposition to new constructions is linked to the delay in the revolutionary liquidation of capitalism.

The situationist wanted the transformation of the world into one which is in a constant state of revolution and newness, just as F.T. Marinetti had proposed half a century before in his Manifesto of Futurismo. The two tools to perform such a transformation, were detournement and derive. In their 1956 essay wrote Guy Debord and Gil J. Wolman: ‘The detournement was to replace art and the derive was to replace work’.

In 1967, Guy Debord published The Society of the Spectacle (Edition Buchet-Chastel Paris, reprinted in 1971 by Champ-Libre Paris and 1970/77/83 as english-language version by Black&Red Detroit), a book which included ideas of philosophers like Sartre, Lukács and urbanists like Lewis Mumford. It was a collage of dadaism, anarchism and existentialsm.

In 1967, Guy Debord published The Society of the Spectacle (Edition Buchet-Chastel Paris, reprinted in 1971 by Champ-Libre Paris and 1970/77/83 as english-language version by Black&Red Detroit), a book which included ideas of philosophers like Sartre, Lukács and urbanists like Lewis Mumford. It was a collage of dadaism, anarchism and existentialsm.

Debord argued: ‘To make the world a sensuous extension of man rather than have man remain an instrument of an alien world, is the goal of the situationist revolution. For us the reconstruction of life and the rebuilding of the world are one and the same desire. To achieve this, the tactics of subversion have to be extended from schools, factories, universities, to confront the spectacle directly. Rapid transport systems, shopping centers, museums as well as the various new forms of culture and the media, must be considered as targets for scandalous activity.’

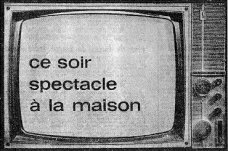

The book dates the critique of everyday life up to describe postwar conditions, where people are held in thrill by a unified media system, which includes TV, newspapers, pop music and culture itself.

‘Culture turned completely into commodity’, wrote Debord in aphorism number 193, ‘must also turn into the star commodity of the spectacular society. In the second half of this century culture will hold the key role in the development of the economy, a role played by the automobile in the first half, and by railroads in the second half of the previous century’.

‘Culture turned completely into commodity’, wrote Debord in aphorism number 193, ‘must also turn into the star commodity of the spectacular society. In the second half of this century culture will hold the key role in the development of the economy, a role played by the automobile in the first half, and by railroads in the second half of the previous century’.

But from todays view the computer plays the role as a tool of this development.In the ten years of its existence the SI had about 70 members, some of them were beside Guy-Ernest Debord: Michéle Bernstein (F), Christopher Gray (UK), Jaqueline de Jong (NL), Asger Jorn (DK), Dieter Kunzelmann (D), Guiseppe Pinot-Gallizio (I), Alexander Trocci (UK), Raoul Vaneigem (B), a.o.

During the 60s the SI products and ideas began to find a way into other countries. In the UK on September 1960 the fourth conference of the SI took place.

There were also british members, such as the scottish poet and beat novelist Alex Trocci. Within their own environment the situationist ideas were a part of the actual pop-culture, a philosophical update of pop-art.

One early english response to the SI was on July 1966 the first number of the magazine Heatwave. It contained material from the Provos in Amsterdam and from american anarchist publications as the Rebel Worker.

Some of the writers including co-editor Christopher Gray formed a year later their own group King Mob and published their magazine King Mob Echo. Some art-students, by the names of Malcom McLaren, Jamie Reid and Fred Vermorel, were also involved in a few of the group actions.

The first major opportunity for the SI arose in 1966 at Strasbourg University. Five pro-situationist students formed an anarchist appreciation society, infiltrated the student-union, appropriated the union funds for situationist inspired posters and invited the SI to write a critique about the university and the society in general.

The resulting 28-pages pamphlet DE LA MISERE EN MILIEU ETUDIANT (original text in french-language / english version) was designed to wind up their obedient to the family and the state: ‘The university has become a -institutional- society for the propagation of ignorance; meanwhile the ‘high skills’ get dissolved in the rhythm of mass-production by the professors, which are all without exception idiots …’

With the student-union funds 10’000 copies of the pamphlet were printed and handed out at the official inauguration-ceremony of the Strasbourg academic year. The reaction was an immediate outcry. The press condemned the action as an incitement to violence. The responsible students were expelled of the university and the student union closed by court order.

At first it seemed the events in Strasbourg didn’t have much effect. But in the following months the ideas of the SI spread out to the universities of France.

Due to overcrowded universities students were allocated to other places. One of these universities was in Nanterre-Paris, where the students lived in small accommodations. Males and females seperated, no recreational facilities and everything controlled by a centralized bureaucracy.

The students demanded reforms, without success! Then they pressed on with claims they knew they would be rejected. Additional they began disrupting lectures and breaking down all communication between lecturers and students. The ensuing disorder escalated by the rumour that plain-clothes police had infiltrated the campus to compile a black-list of trouble-makers. The students-union protested and the situation was developing …

The involved students became known as Les Enrages, because of their theatrical nature and violence, and called after a group of the French Revolution. On March 22nd 1968, as a protest against the arrest of five members of the National Committee For Vietnam, a group of Les Enrages and some anti Vietnam-War demonstrators occupied the university-administration offices. The movement of March 22nd was born, an organization with no hierarchy and no ideological programm. There were members of various groups but also non-organized students.

The involved students became known as Les Enrages, because of their theatrical nature and violence, and called after a group of the French Revolution. On March 22nd 1968, as a protest against the arrest of five members of the National Committee For Vietnam, a group of Les Enrages and some anti Vietnam-War demonstrators occupied the university-administration offices. The movement of March 22nd was born, an organization with no hierarchy and no ideological programm. There were members of various groups but also non-organized students.

Dany Cohn-Bendit soon established himself as the principal spokesman; describing himself as ‘a megaphone for the movement and an anarchist by the negation of authoritarian hierarchies as communism and capitalism’.

Cohn-Bendit and the situationists wanted central coordinated worker/student-councils, who act together but preserve their autonomy.

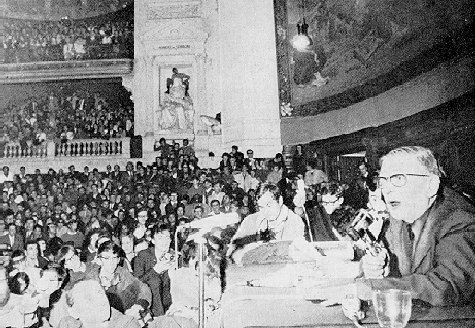

The Sorbonne was transformed from an institutionalized bureaucracy to ‘a volcano of revolutionary ideas’. Day and night in every lecture hall were passionate discussions. The spirit of the Paris Commune was back …

It was the time where the slogans, later reused by the punk-movement, were written on the walls:

- GO AND DIE IN NAPLES WITH THE CLUB MEDITERRANEE

- BE REALISTIC DEMAND THE IMPOSSIBLE

- TAKE YOUR DESIRES FOR REALITY

- REFUSE YOUR ASSIGNED ROLES

- NEVER WORK

- CONSUMPTION IS THE OPIUM OF THE PEOPLE

- THEY ARE BUYING YOUR HAPPINESS, STEAL IT

- ART IS DEAD: DO NOT CONSUME ITS CORPSE

- UNDER THE PAVEMENT THE BEACH

Members of the Situationist International, Les Enrages and some others were forming The Council For The Maintenance Of The Occupation. Their aim was to set up action committees to spread out the sit-in’s and strikes from Paris to the rest of France.

By May 21st 1968 10 million french workers were on strike, most factories were occupied and the french transport system was brought to a standstill.

But the communist party and their trade union CGT refused the further support of this revolt, because their central committee had no control over the movement … a similar situation as 32 years ago in spain, as the communists ‘helped’ the fascists to destroy the spanish republic.

This general strike was the most serious crises for the french government since World War II. De Gaulle got the assistance of the army, dissolved the parliement and ordered new elections which were won by the bourgois parties.

But the May’68 in Paris showed, that the situationist idea of intervening a situation with deliberate and systematic provocation functionated very effective.

Another important experience was, that in the answering of the power-question all parties were/are equal. They showed their true face when they opposed against the anti-hierarchy and self-management organisation of the 22nd March Movement.

‘People who talk about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal or constraints, such people have a corpse in their mouth.’

Raoul Vaneigem: The Revolution Of Everyday Life