Jamie Reid

Born in 1947 as the son of Nora (nee Gardner) and John MacGregor Reid. Both parents were steeped in socialism and left-leaning politics, and had first met at a Labour party rally in the 1920s.

Jamie Reid had been brought up in Shirley, the thirties 'dream suburb' east of Croydon. It is a neat environment, which at the time it was built accorded with the spatial fantasy of that time: sub-urbanism. 'In principle it’s a very good system,' Reid says, 'why shouldn’t everybody have their own garden? But I’ve always had a love/hate relationship with suburbia: I hate what it’s become.'

Jamie had gone straight to Wimbledon Art School from John Ruskin Grammar School, where he was an unwilling student. It had been a toss-up between art and football, but painting won: Reid was obsessed by Jackson Pollock, whose canvases he saw as landscapes. At Wimbledon, the teaching methods were very traditional and Reid rebelled: 'I was a typically obnoxious young art student.' He was ready for Croydon Art School which offered more freedom: full of the romanticism of painting, he started there in autumn 1964.

Jamie had gone straight to Wimbledon Art School from John Ruskin Grammar School, where he was an unwilling student. It had been a toss-up between art and football, but painting won: Reid was obsessed by Jackson Pollock, whose canvases he saw as landscapes. At Wimbledon, the teaching methods were very traditional and Reid rebelled: 'I was a typically obnoxious young art student.' He was ready for Croydon Art School which offered more freedom: full of the romanticism of painting, he started there in autumn 1964.

The near-revolution that occured in Paris and the rest of France during May 1968 had an immediate impact on youth throughout the world: partly because it was the first televised urban insurrection, partly because it marked a generation claiming its political rights.

The most identifiable signs in Paris of 1968 were posters and graffiti inspired by the Situationist International. Their cryptic phrases were the perfect medium for this revolt. Slogans like DEMAND THE IMPOSSIBLE or IMAGINATION IS SEIZING POWER inverted conventional logic: they made complex ideas suddenly seem very simple. For the bored students in Croydon, the revolt at the Sorbonne in Paris acted as a starting pistol. Some students, beneath them Malcolm McLaren and Jamie Reid, were involved in a sit-in that developed in Croydon. On 5 June, the art students barricaded themselves in the annexe at South Norwood and issued a series of impossible demands.

'The idea was in the air,' says Jamie Reid; ‘at the time it was imperative just to contribute to what was going on and take your own action. There was a genuine contact between the Sorbonne, Croydon and Hornsey.’ The action was above all a media event. But for Jamie Reid and his associates like Fred Vermorel and Malcolm McLaren, it was an eye-opener: 'I went from a student worrying about his little niche into being someone who was very aware of what was happening in other parts of the world – what was taking place in Paris, the riots in Watts. I really felt that I had control over my own life and over my environment.' They learned a language to articulate their angers and their ideals.

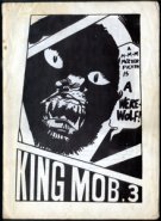

One early english response to the SI was a magazine called Heatwave. Some of the writers including co-editor Christopher Gray formed a year later in 1968 their own group King Mob and declared themselves and their politics through their tabloid magazine King Mob Echo. The group took their name from Christopher Hibbert’s book (1958) on the Gordon Riots of June 1780, the anarchic week that was akin to the French Revolution a few years later. In applauding this hidden moment in British history, the group were attempting to reemphasize a disordered, anarchic Britain that had previously been swept under the carpet. It was an attempt to give a specifically British context to the growing discontent. Some Croydon art-students, by the names of Malcom McLaren, Jamie Reid and Fred Vermorel, were also involved in a few activities.

One early english response to the SI was a magazine called Heatwave. Some of the writers including co-editor Christopher Gray formed a year later in 1968 their own group King Mob and declared themselves and their politics through their tabloid magazine King Mob Echo. The group took their name from Christopher Hibbert’s book (1958) on the Gordon Riots of June 1780, the anarchic week that was akin to the French Revolution a few years later. In applauding this hidden moment in British history, the group were attempting to reemphasize a disordered, anarchic Britain that had previously been swept under the carpet. It was an attempt to give a specifically British context to the growing discontent. Some Croydon art-students, by the names of Malcom McLaren, Jamie Reid and Fred Vermorel, were also involved in a few activities.

In the first quarter of 1970, Jamie Reid worked with Malcolm McLaren on the history of 'Oxford Street' 'as a set of attractions; respectability is invented for people to better themselves as they pay highly for it'. Their version traced the history of Oxford Street from Tyburn at Marble Arch on the western end: the hangings on Monday, execution day, were 'London’s largest free spectacle'. The street was slowly taken over by the middle class: in 1760, the Pantheon opened, a fashionable amusement palace where one lady dressed 'one half of herself smart and other half in rags'. Their account of the Gordon Riots begins: 'the middle class started it against the Catholics. Then hundreds of shopkeepers, carpenters, servants, soldiers and sailors rushed into the streets. There were only a few Catholic houses to smash. So they started to smash all the rich houses. The middle classes did not want anything to do with this.' The rioters then 'burned down all five London prisons. They wanted to knock down everything that stopped them having fun and made them unhappy. They wanted to set all the mad people free and free the lions from the Tower.' The film was still not finished.

His lettering mimicked the cut-and-paste style of an anonymised ransom note, a style he first developed with the countercultural publication Suburban Press, which he began in 1970 alongside Jeremy Brook and Nigel Edwards, what was in Jamie’s words 'very Anarchist, Situationist based'. They produced their own posters and magazines and printed leaflets for squatting movements, prisoner’s rights, the black movement and feminist women’s groups. Jamie Reid familiarized himself with libertarian thinkers like Charles Fourier and published toughts of british anarchists like William Morris and Digger Gerrard Winstanley.

As the Suburban Press had to produce 'really fast, quick, powerful, agitprop-type' on a tiny budget, it was necessary to improvise. They cut out letters from newspapers and photographs and 'used the whole sort of ripped and torn punk-image.' In 1974, Jamie Reid designed and printed the first english-language anthology of the Situationists, Christopher Gray’s translation of SI texts Leaving the 20th Century.

As the Suburban Press had to produce 'really fast, quick, powerful, agitprop-type' on a tiny budget, it was necessary to improvise. They cut out letters from newspapers and photographs and 'used the whole sort of ripped and torn punk-image.' In 1974, Jamie Reid designed and printed the first english-language anthology of the Situationists, Christopher Gray’s translation of SI texts Leaving the 20th Century.

Then in 1976 Malcolm McLaren, now the manager of a band called the Sex Pistols, send a telegram to Jamie Reid: 'Got these guys, interested in working with you again.' Reid’s stint as the Sex Pistols art director would result in the most provocative designs of the rock-music. Jamie Reid says: 'It wasn’t the phenomen that interested me. I saw punk as a part of an art movement that’s gone over the last hundred years, with roots in Russian agitprop, surrealism, dada and situationism. We used to talk to John (Rotten/Lydon) a lot, about the Situationists, about Suburban Press. The Sex Pistols seemed the perfect vehicle to communicate ideas directly to people who weren’t getting the message from left wing politics.'

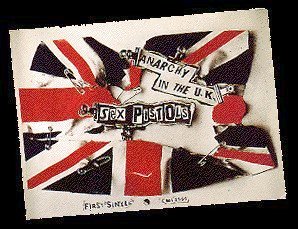

Whatever their precise provenance, the ringing phrases of the first Pistols Single Anarchy in the UK were powerful enough to insert the idea of anarchy into a new youth culture called Punk.

On October 1976 Glitterbest and EMI signed a two-year contract for the Sex Pistols. Anarchy in the UK should be the first Sex Pistols single. The idea behind it was strong: The song was nothing less than a manifesto for the group’s entry into public life. The presentation of the single had to be handled carefully. Group photos were rejected as clichéd by Glitterbest under their contractual veto: instead of it, they decided to use record-sleeves and posters to articulate the ideas behind the Sex Pistols. Reid and McLaren came up with an idea devasting in its simplicity – a plain, shiny black bag. 'The idea, to have no identity, was very anarchic,' says McLaren. For the poster, Reid tore up a Union Jack souvenir flag and reassembled it with safety-pins.

On October 1976 Glitterbest and EMI signed a two-year contract for the Sex Pistols. Anarchy in the UK should be the first Sex Pistols single. The idea behind it was strong: The song was nothing less than a manifesto for the group’s entry into public life. The presentation of the single had to be handled carefully. Group photos were rejected as clichéd by Glitterbest under their contractual veto: instead of it, they decided to use record-sleeves and posters to articulate the ideas behind the Sex Pistols. Reid and McLaren came up with an idea devasting in its simplicity – a plain, shiny black bag. 'The idea, to have no identity, was very anarchic,' says McLaren. For the poster, Reid tore up a Union Jack souvenir flag and reassembled it with safety-pins.

His posters and record sleeves, he says, were designed 'to articulate ideas, many of which were anti-establishment and quite theoretical and complicated.' Reid often appropriated and subverted familiar images; posters for the Pistols’ single God Save the Queen, depict the queen of England with a safety pin through her lips.

For the next Pistols-single, the first on A&M, the record-company worked up cover roughs which showed the group in front of Buckingham Palace. Glitterbest, however, planned a brilliant campaign that drew on all aspects of Jamie Reid’s experience and knowledge about the situationism. The single was to be released without a picture cover, but a whole series of images had been worked out for accompanying media: handbills, posters, adverts and stickers which were already being handed out. It was Reid’s first integrated campaign.

'I must have done literally hundreds of different images around that official Cecil Beaton portrait. I did two days of sessions with photographer Carol Moss until I came up with the safety-pin through her mouth. There was no point in beating about the bush; you use the same tactics that you know are going to get thrown back in your face from the likes of the Mirror and the Sun. The safety-pin image wasn’t banned at A&M, although the one where she has swastikas over her eyes was.'

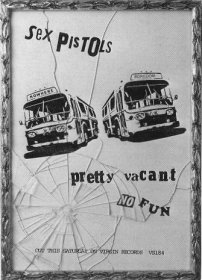

During the Berlin trip in 1977 the Sex Pistols had written a new song, Holidays in the Sun, but it wasn’t ready. So McLaren and Reid decided to go with Pretty Vacant: It was catchy, already very popular with the fans and lyrically uncontroversial. It was one of the Sex Pistols’ earliest songs and the most obviously anthemic, with its simple but dramatic repeated-chord opening and its inclusive chorus line.

During the Berlin trip in 1977 the Sex Pistols had written a new song, Holidays in the Sun, but it wasn’t ready. So McLaren and Reid decided to go with Pretty Vacant: It was catchy, already very popular with the fans and lyrically uncontroversial. It was one of the Sex Pistols’ earliest songs and the most obviously anthemic, with its simple but dramatic repeated-chord opening and its inclusive chorus line.

Despite the haste with which it was planned, Pretty Vacant was a charged, complicated package, from the Situ-picture sleeve through to the burned out version of No Fun on the B-side.

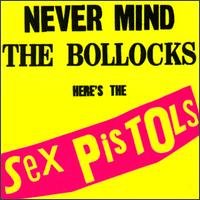

Shortly afterwards, the title and the cover concept for the following Sex Pistols album had been decided. Initial versions had been called God save the Sex Pistols, and Jamie Reid had worked up some proofs in vivid yellow and dark red. There were to be again no picture of the group, just cut-out lettering with a coarse resolution reminiscent of screen-prints. During the summer the album became the name Never Mind the Bollocks, a phrase supplied by Steve Jones.

To keep up the attention, Holidays in the Sun was pulled out of the hat as a fourth single. McLaren and Reid worked up another campaign with a video (never shot) that would be a ‘re-creation of the TV ads used by the Sun and the News of the World to advertise holiday features’. This was the heyday of the Sex Pistols’ graphic image. Under pressure, Reid went public his Situationist connections. The front cover of the sleeve was a modified belgian holiday brochure, which had cartoon illustrations of a typical family on a typical holiday. Reid inserted the song lyrics into the cartoon bubbles in the same way as the Situationists had done it with detectives comics.

To keep up the attention, Holidays in the Sun was pulled out of the hat as a fourth single. McLaren and Reid worked up another campaign with a video (never shot) that would be a ‘re-creation of the TV ads used by the Sun and the News of the World to advertise holiday features’. This was the heyday of the Sex Pistols’ graphic image. Under pressure, Reid went public his Situationist connections. The front cover of the sleeve was a modified belgian holiday brochure, which had cartoon illustrations of a typical family on a typical holiday. Reid inserted the song lyrics into the cartoon bubbles in the same way as the Situationists had done it with detectives comics.

For the reverse, he pulled out an illustration from Suburban Press, called the Nice Drawing, and simply added the Satellite lettering from the 100 Club poster of the previous year. For the music press ads and large posters, Reid took a graphic he had contributed to Chris Gray’s 1974 translation of Situ texts, adding speech bubbles and an old Suburban Press sticker: Keep warm this winter, make trouble.

On 28th October 1977, the Sex Pistols album Never Mind the Bollocks – Here’s the Sex Pistols was rush-released, two weeks before the worldwide release was scheduled. Glitterbest had already shipped tapes to the french licensing partner Barclay and, as a further delaying device, insisted that Virgin add Submission to the eleven tracks already pressed. In the last week of October, Virgin learned of Barclays’ plan to export copies into England ahead of the release date, and Virgin rush-released the album.

On 28th October 1977, the Sex Pistols album Never Mind the Bollocks – Here’s the Sex Pistols was rush-released, two weeks before the worldwide release was scheduled. Glitterbest had already shipped tapes to the french licensing partner Barclay and, as a further delaying device, insisted that Virgin add Submission to the eleven tracks already pressed. In the last week of October, Virgin learned of Barclays’ plan to export copies into England ahead of the release date, and Virgin rush-released the album.

With Bodies, the title and the already banned God Save the Queen, the album was banned by Boots, Woolworths and W.H.Smith. The advance orders of more than 150’000 were enough to bring it straight into the charts as the unequivocal number one. It was a near repeat of God Save the Queen, but unlike in June, this time it was a full stop, then the group would never record together again. Then in 1979, the release of the film The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle and the soundtrack as a double-album. The film’s opening images of ragged Punks in the Gordon Riots reemphasized the covert but powerful english tradition of disorder, already highlighted by God Save the Queen with results that still reverberate. ‘In the end,’ says Jamie Reid, ‘it was our fault that we didn’t articulate our ideas well enough.’ Despite McLaren’s and Reid’s libertarian intent, The Great Rock’n’Roll Swindle became swamped, as their wish to destroy what they had created fused with the cynicism of the time.Jamie Reid’s work demonstrated the power of graphic design in the music industry and opened the door to a strong new generation of British designers, whose purpose was different from Jamie’s. They used the creative freedom of the music industry as a showcase for vibrant design, unaffected by corporate compromise. Their influence has spread beyond music to fashion, the media and consumer packaging.

In the following years Jamie Reid worked for political movements – the anti-Poll Tax and anti-Criminal Justice Act campaigns are just two of those who have benefited from his unique style of visual anarchy – and punk bands such as the Dead Kennedys or 2018 Pussy Riot.

In 1989 Reid designed the poster for the ICA’s (London’s Institute of Contemporary Art) touring retrospective of the Situationist International, which appropriates the front cover of Reid’s and Grey’s Leaving the 20th Century and dates the SI from 1957 to 1972!

Peace is Tough a touring exhibition of Reid’s work, started in 1989 when a gallery in Tokyo asked him to do a retrospective. It was only the second exhibition that he had ever done and he decided to keep it on the road. And ten years later the exhibition was still to see in arts centres.

Reid says punk is still relevant today and the DIY idea has never really gone away. People still have to get out and do things for themselves, particularly 'people who haven’t the privilege of money or access to the education system'. Reid himself left the school at the age of 16 – in today’s world he would probably not have had a chance of getting into art college.

He explained his ethos in 2015: 'Our culture is geared towards enslavement – for people to perform pre-ordained functions, particularly in the workplace. I’ve always tried to encourage people to think about that and to do something about it.' Jamie Reid died on 8. August 2023. R.I.P.